What is art? The word art is used today to describe a wide variety of things from prehistoric cave paintings to those apparently nonsensical installations you find in modern galleries. Music and literature are also art but here we’re going to consider visual art only.

Is visual art made to be looked at? Is it made for spiritual purposes? Is it made just as a creative outlet? Does art have as many meanings as the artists who make it? Should art be beautiful or just a capture of human emotions? Is art made just for its own sake or to express ideas? Does it have to provoke a reaction?

What art is has always been at the centre of a great debate, to the point that often this led to violent disputes, like when in 1870 Manet challenged the critic Duranty to a sword duel.

This book tries to describe specifically what the Upper Paleolithic cave art is, by investigating why the people of that period made those images, deep-inside the earth, in totally dark and difficult-to-access places, and what they meant to them.

The author is David Lewis-Williams, a South African archaeologist and a university professor of cognitive archaeology. To explain prehistoric art, he analyses the development of the human mind.

I was hooked on the paragraph that examined, according to Steven Mithen, professor of archaeology at the University of Reading, what the different kinds of intelligence are in the evolution of the human mind,

Lewis-Williams moves some critics to this theory by believing that, as attractive as it is, Mithen’s view has weakness in marginalizing the importance of the full range of human consciousness in human behaviour.

Then comes my favourite part of the book, where the author proceeds to examine the spectrum of consciousness. This, according to Lewis-Williams, at a certain point, is divided into:

1) “ordinary consciousness” which drifts from alert to somnolent states

and

2) “intensified trajectory” which leads to hallucinations.

The former is considered the “good” one, while the latter is considered “altered” – both of them, all parts of the spectrum, are equally genuine.

The altered states of consciousness can occur in people exposed to sensory deprivation and are influenced by the culture of the period.

According to Lewis-Williams, the brains of the homo sapiens of that period were fully modern as those people were experiencing the full spectrum of human consciousness including dreaming and the potential to hallucinate. He thinks the same cannot be said of the homo neanderthalensis though and explains why.

The author speculates that in all of the hunter-gatherer Upper Paleolithic communities there were shamans who used to enter altered states of consciousness (by sleep deprivation or by taking hallucinating substances) and make sense of the resultant hallucinations by producing cave art. They were probably trying to get in contact with the animal spirit.

This is what cave art represented for the Upper Paleolithic humans – it wasn’t art for art’s sake, but it was linked to the stages of altered consciousness of shamans and to their resulting mystical experience, in order for them to establish their power and maintain their leadership in their communities.

The tone and the structure of the book are academic, which I really enjoyed as it reminded me of my university days, and the enthusiasm of the author is contagious. In the book, there are also many illustrations and some practical case studies, which I appreciated too as this helped in approaching the topics.

In Conclusion

The author’s thesis is too technical for a layperson so I don’t have enough knowledge to form my own opinion about it or to make my observations about how he develops his views, nonetheless, it’s seductive and thought-stimulating. I’ve acquired lots of archaeological information and am overall fascinated by this challenging and interesting read.

Some of My Favourite Quotes From the Book:

Consciousness. We all know what it means – until someone asks us to define it.

If we are speaking of evolution, we are speaking – essentially – of the human body, our physical, material make-up of bones, blood, tissue, brain matter. By contrast, mind is a projection, an abstraction; it cannot be placed on a table and dissected as can a brain.

Despite the current plethora of studies of human consciousness, we still do not know how the functioning of the brain produces human consciousness.

Consciousness is like religion: if you have it, you cannot study it. Put another way, our cognitive abilities do not allow us to understand our cognitive abilities.

Title: The Mind in the Cave – Consciousness and the Origins of Art

Author: David Lewis-Williams

Year first published: 2002

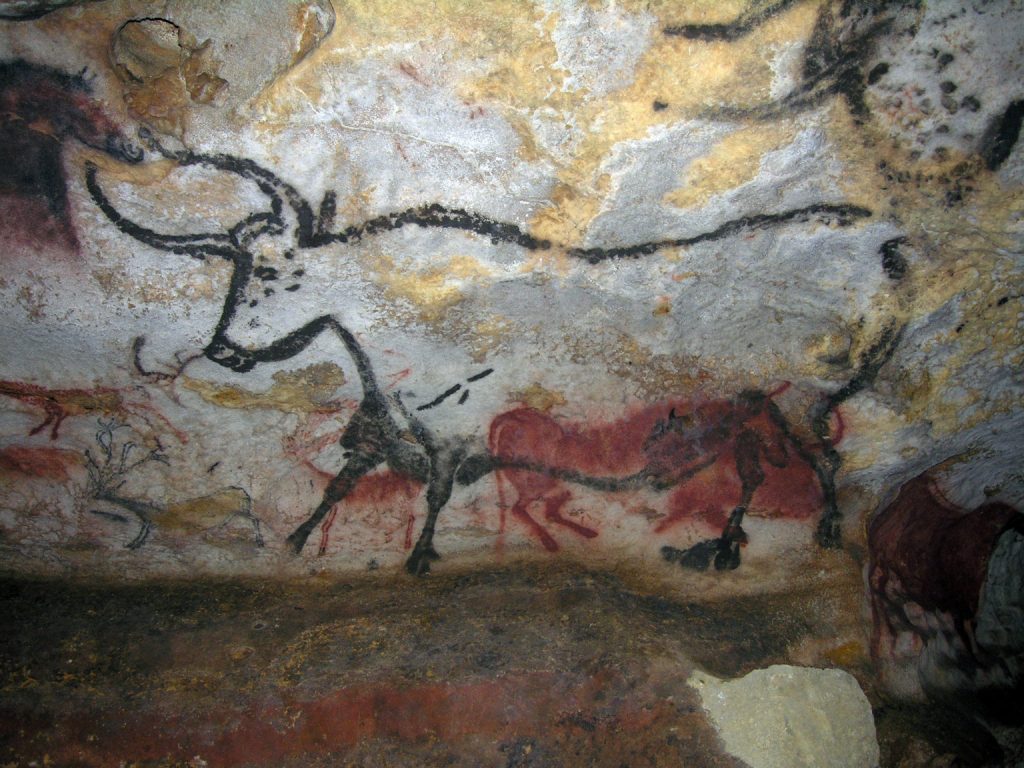

Emerging from the narrow underground passages into the chambers of caves such as Lascaux, Chauvet, and Altamira, visitors are confronted with symbols, patterns, and depictions of bison, woolly mammoths, ibexes, and other animals.

Since its discovery, cave art has provoked great curiosity about why it appeared when and where it did, how it was made, and what it meant to the communities that created it. David Lewis-Williams proposes that the explanation for this lies in the evolution of the human mind. Cro-Magnons, unlike the Neanderthals, possessed a more advanced neurological makeup that enabled them to experience shamanistic trances and vivid mental imagery. It became important for people to “fix,” or paint, these images on cave walls, which they perceived as the membrane between their world and the spirit world from which the visions came. Over time, new social distinctions developed as individuals exploited their hallucinations for personal advancement, and the first truly modern society emerged.

Illuminating glimpses into the ancient mind are skillfully interwoven here with the still-evolving story of modern-day cave discoveries and research. The Mind in the Cave is a superb piece of detective work, casting light on the darkest mysteries of our earliest ancestors while strengthening our wonder at their aesthetic achievements.